Revelations about what this practice is about can be delivered from unexpected, and even startling, corners.

In his sensory-drenched 1956 autobiographical memoir, And There Was Light, Jacques Lusseyran reflects about seeing and sensing the radiance of the world while living most of his life with eyes that couldn't see. Blinded in an accident as a young child, Lusseyran shares how he came to experience his world in light, "existing through it and because of it."

He was delighted that the colors of the rainbow survived for him after he was blinded, but colors were, in his words, "only a game."

Light became his reason for living.

He wrote:

"I let it rise in me like water in a well, and I rejoiced. A light so continuous and so intense was so far beyond my comprehension that sometimes I doubted it. Suppose it was not real, that I had only imagined it. Perhaps it would be enough to imagine the opposite, or just something different, to make it go away. So I thought of testing it out and even of resisting it."

As a child, and later as an adult, he experimented using his willpower to stop the flow of light. He could not:

"At eight I came out of this experiment reassured, with the sense that I was being reborn. Since it was not I who was making the light, since it came to me from outside, it would never leave me. I was only a passageway, vestibule for this brightness. The seeing eye was in me."

Less than a year after Germany's 1940 invasion of his native France, Lusseyran and his friends formed a student resistance group, the Volunteers of Liberty. As word got out to the secondary schools and universities about the secret movement, he vetted prospective new members — over 600 in one year — who wanted to join.

"Go see the blind man," they were told.

His gift for acute sensory awareness translated into almost foolproof accuracy when it came to 'reading' who was trustworthy and who was not. Lusseyran listened with great care to words and for silences to sort out who was sincere and who was not.

He went on to become a leader of the French resistance but was betrayed by the one person whom he had admitted to the movement against his better judgment. Lusseyran and his friends were arrested by the Gestapo and shipped to a Nazi concentration camp in July 1943. He was liberated from Buchenwald in 1945 and was among just 30 survivors out of the 2,000 who had been arrested along with him. He went on to lead a rich, but short, life as an author and a professor until his accidental death in 1971.

As Lusseyran navigated through times doused with fear and fierce inhumanity, his fealty was to the wisdom and solace that light offered him.

His was a lifelong and sacred dance with light.

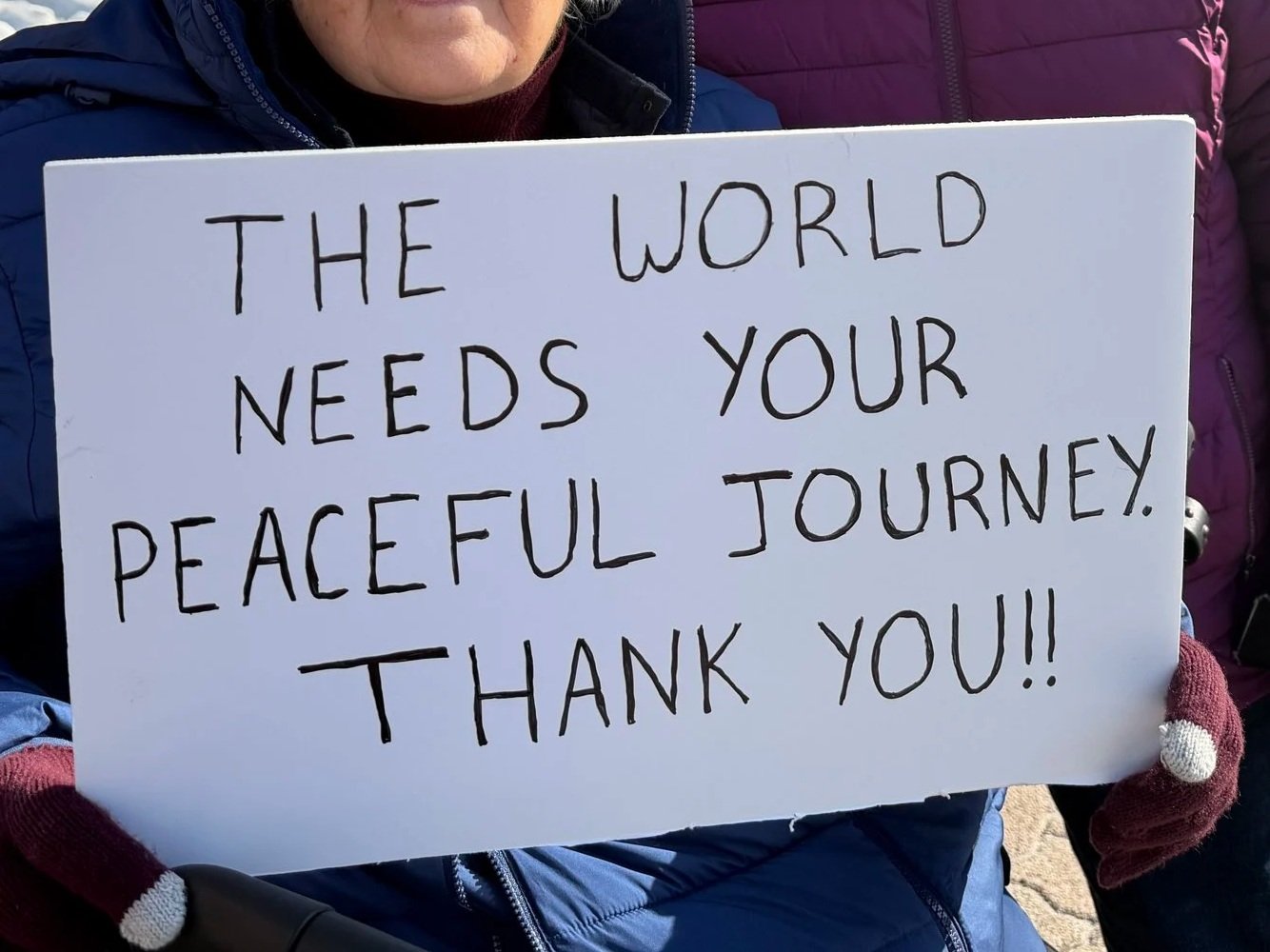

Many of us feel stuck in the spin cycle in these wobbly times. But maybe one lesson from Lusseyran is that we don't need to chase light or get overzealous about dominating it. Giving in to the temptation to demand and grasp for goodness can be exhausting and unsatisfying.

Here's an avenue of inquiry. What if we manage, now and again, to regard ourselves as natural "vestibules for brightness"? Can we become better skilled at leaving behind habits that block our experience of ongoing radiance? Can our actions and our practice then transform our experience of life and ripple out more meaningful action in the world?